My American roots trio has been practicing “Idumea,” one of my favorite shape note songs. “Shape note” signifies a type of shape-based musical notation popular in the early 1800s; shape note hymns reveal much about people’s beliefs concerning religion, mortality, and an afterlife during that era.

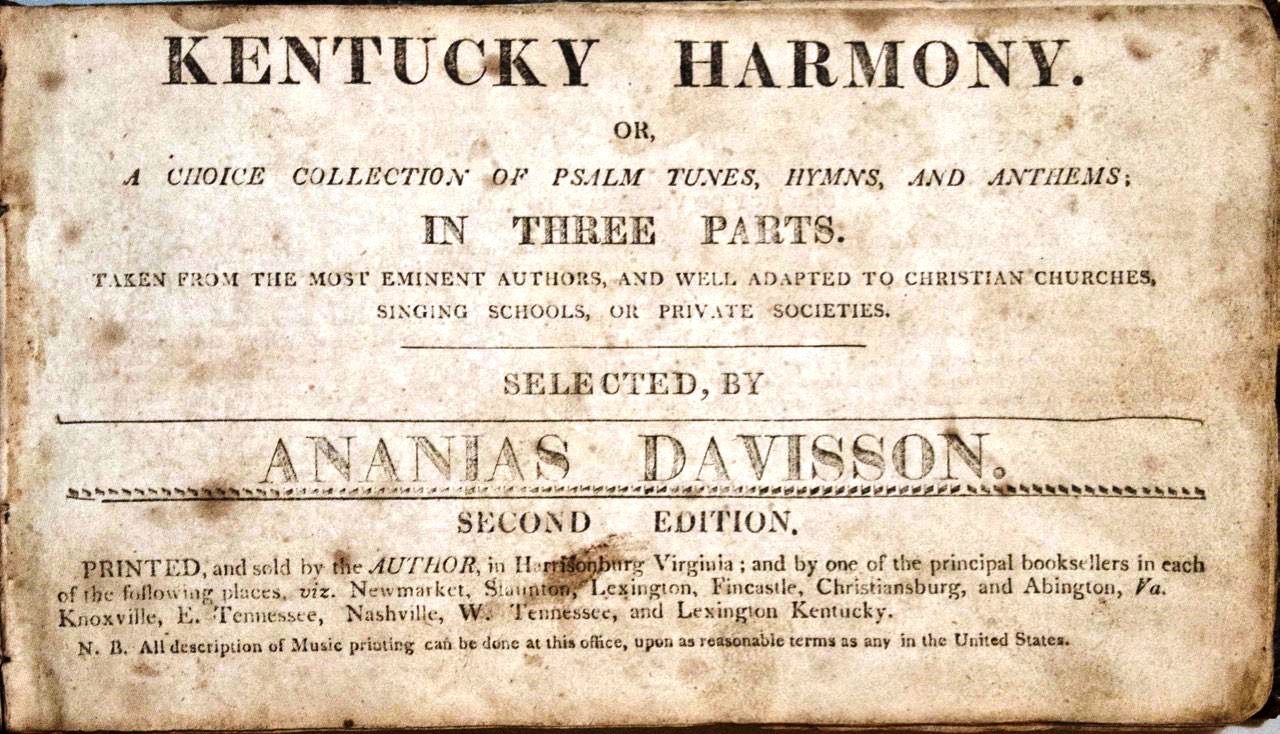

The spare, minor-mode harmony in “Idumea” sends shivers up and down my spine. The music was composed by Ananias Davisson, a Virginian. Initially Davisson printed it with poetry by the English cleric Isaac Watts (1674-1748) in his 1816 tune book Kentucky Harmony. Almost twenty years later, William Walker included “Idumea” in his 1835 Southern Harmony, pairing Davisson’s music with different lyrics that begin: “And am I born to die? To lay this body down? And must my trembling spirit fly into a world unknown?” These portentous words are by Charles Wesley (1707-1788), another English preacher and a leader in the Methodist religious movement.